Gouaches

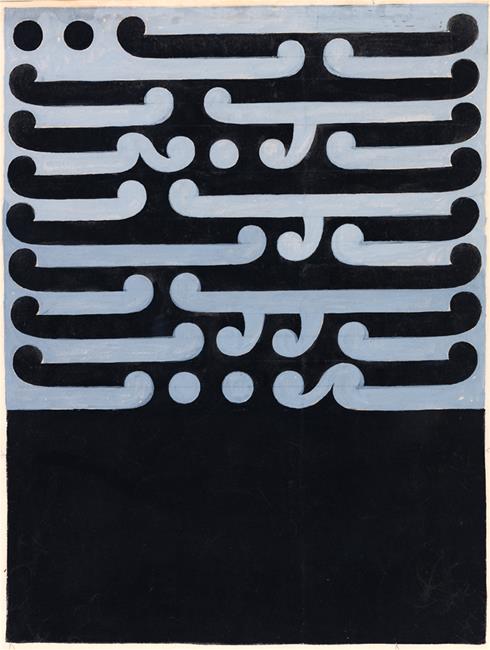

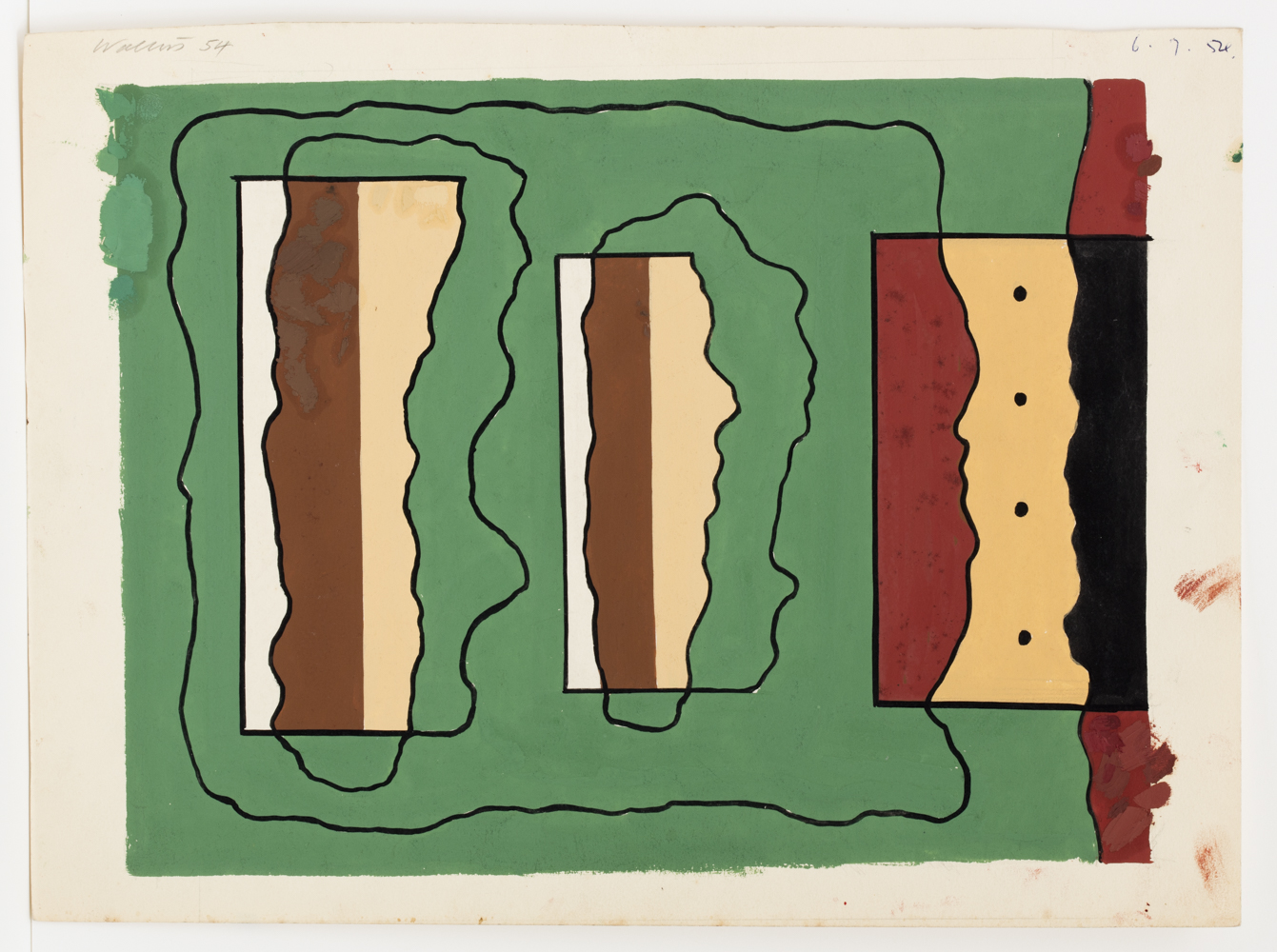

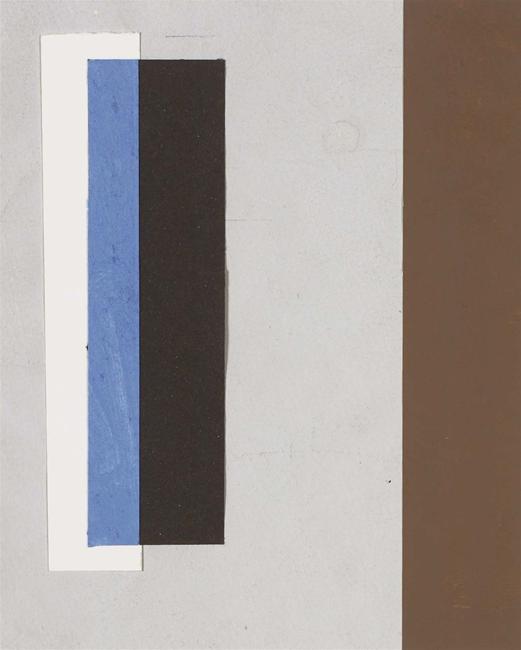

There are three important sources that inform Walters’ gouache works, which were mostly painted over a decade at night while he worked for the Government Printing Office during the day. First of all, Walters had worked his way aboard ship to London in 1950. In 1951 on a continental excursion, he was exposed first-hand to the geometrical abstractions of Auguste Herbin, Alberto Magnelli and Victor Vasarely at the Denise René Gallery in Paris; and then the works of Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg in The Hague, Rotterdam and Amsterdam. Secondly, into this heady engagement with European modernity upon his return to New Zealand Walters was to inject his prior interest in the field of Maori rock art. During the summer of 1946-47 he had worked closely alongside Indonesian expatriate Theo Schoon recording Maori rock drawings in the limestone bluffs and shelters of South Canterbury, places which Schoon majestically described as ‘New Zealand’s oldest art galleries’. The rock-art depiction of human and animal figures with blank centres inspired the geometry and interlocking structures of stylized anthropomorphic figures that were to appear later in many of Walters’ gouaches. Thirdly, in 1953 Schoon had also introduced Walters to the work of Rolfe Hattaway, a permanently hospitalised psychiatric patient whose drawings made with a lump of clay on the asphalt of an exercise yard had captivated Schoon when employed as an orderly at the Avondale psychiatric hospital. Schoon provided Hattaway with art materials and later he and Walters copied Hattaway’s loopy tumults of line, in particular the repeated motif of a long open rectangle penetrated by a curving snake-like form. The importance for Walters of this positive form penetrated by a negative emptiness was now confirmed for him from an arresting double source: rock art and outsider art. These two tours de force dramatise the radical aesthetics of Walters’ fifties gouaches that willfully blur the differences between abstraction and nature.

Walters’ rapid study gouaches of the 1950s called for a certain tenacity of purpose, sustained analysis and prolonged concentration. They yielded a surprising narrative of astonishing range, providing images and compositions that would carry Walters through the decades to follow. Years later he was still using motifs he had stored in his visual memory from the fifties. For the paradox remains that in such an elaborated intellectual practice of painting as Walters’ so many of the key effects and decisions are derived from moments of pure coincidence and inspiration. Walters’ best works of this period are permanently embroiled in the present tense of their making; they would be just as fresh as if created today or tomorrow.

Laurence Simmons, September 2015

Gouaches

There are three important sources that inform Walters’ gouache works, which were mostly painted over a decade at night while he worked for the Government Printing Office during the day. First of all, Walters had worked his way aboard ship to London in 1950. In 1951 on a continental excursion, he was exposed first-hand to the geometrical abstractions of Auguste Herbin, Alberto Magnelli and Victor Vasarely at the Denise René Gallery in Paris; and then the works of Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg in The Hague, Rotterdam and Amsterdam. Secondly, into this heady engagement with European modernity upon his return to New Zealand Walters was to inject his prior interest in the field of Maori rock art. During the summer of 1946-47 he had worked closely alongside Indonesian expatriate Theo Schoon recording Maori rock drawings in the limestone bluffs and shelters of South Canterbury, places which Schoon majestically described as ‘New Zealand’s oldest art galleries’. The rock-art depiction of human and animal figures with blank centres inspired the geometry and interlocking structures of stylized anthropomorphic figures that were to appear later in many of Walters’ gouaches. Thirdly, in 1953 Schoon had also introduced Walters to the work of Rolfe Hattaway, a permanently hospitalised psychiatric patient whose drawings made with a lump of clay on the asphalt of an exercise yard had captivated Schoon when employed as an orderly at the Avondale psychiatric hospital. Schoon provided Hattaway with art materials and later he and Walters copied Hattaway’s loopy tumults of line, in particular the repeated motif of a long open rectangle penetrated by a curving snake-like form. The importance for Walters of this positive form penetrated by a negative emptiness was now confirmed for him from an arresting double source: rock art and outsider art. These two tours de force dramatise the radical aesthetics of Walters’ fifties gouaches that willfully blur the differences between abstraction and nature.

Walters’ rapid study gouaches of the 1950s called for a certain tenacity of purpose, sustained analysis and prolonged concentration. They yielded a surprising narrative of astonishing range, providing images and compositions that would carry Walters through the decades to follow. Years later he was still using motifs he had stored in his visual memory from the fifties. For the paradox remains that in such an elaborated intellectual practice of painting as Walters’ so many of the key effects and decisions are derived from moments of pure coincidence and inspiration. Walters’ best works of this period are permanently embroiled in the present tense of their making; they would be just as fresh as if created today or tomorrow.

Laurence Simmons, September 2015